- Home

- Jane Smiley

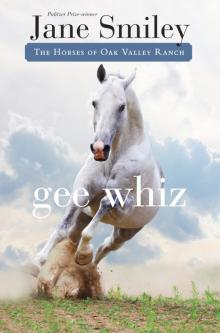

Gee Whiz

Gee Whiz Read online

ALSO BY JANE SMILEY

The Georges and the Jewels

A Good Horse

True Blue

Pie in the Sky

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2013 by Jane Smiley

Illustrations copyright © 2013 by Elaine Clayton

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Visit us on the Web! randomhouse.com/kids

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at

RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Smiley, Jane.

Gee Whiz / Jane Smiley; with illustrations by Elaine Clayton. — 1st ed.

p. cm.

(The horses of oak valley ranch; bk. 5)

Summary: Soon after her yearling, Jack, begins working with professional trainers at a nearby ranch, Abby Lovitt takes responsibility for a very large, very smart, and very curious retired racehorse named Gee Whiz.

ISBN 978-0-375-86969-3 (trade) — ISBN 978-0-375-96969-0 (lib. bdg.) — ISBN 978-0-375-98533-1 (ebook)

[1. Horses—Training—Fiction. 2. Ranch life—California—Fiction.

3. Family life—California—Fiction. 4. Christian life—Fiction.

5. California—History—1950—Fiction.] I. Clayton, Elaine, ill. II. Title.

PZ7.S6413Gee 2013

[Fic]—dc23

2012024370

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Epilogue

About the Author

Chapter 1

MY PLAN WAS TO LET BLUE AND JACK PLAY FOR TEN OR FIFTEEN minutes, then to catch Blue and tack him up, then to ride him in the arena while Jack trotted and wandered about. That way, I would get two horses done in the time it would normally take for one, and I would also get to watch Jack while riding Blue. I had already put Jack in the arena; now I opened the gate again and walked in with Blue. Jack came trotting over to us, his neck arched and his ears pricked. His tail was arched, too. I took off Blue’s halter and they sniffed each other, then Blue trotted away as if he were interested in every other thing in the arena but Jack. Jack trotted behind him.

Jack decided to investigate the cones. He went over to one and sniffed it, then snorted and reared a bit, then sniffed it again. He trotted around it, and then stopped and looked at the cone beside it. Blue continued to ignore him—he was looking for bits of grass under the arena fence, walking along with his head down and his nose to the ground. I went to the center of the arena and started straightening the poles that were lying there. It was the last day of November, a cool, breezy day. The grass was beginning to turn green—it was bright-looking and appetizing, but I wondered if it had much flavor, since sometimes the horses spit it out. The quiet lasted for about a minute, then it was as if both horses had the same thought—“What’s he doing?” They turned at the same time, trotted over to one another, and sniffed noses. All at once, Jack reared up and took off along the fence line, and in half a second, Blue went after him. I smiled and continued to push the poles—there were about twelve of them—closer together. The horses galloped for ten strides or so, bucking and squealing. Jack even reared up once, but when they came to the far end of the arena, they turned into real Thoroughbreds—they stopped acting up and started running, and by the time they were halfway down the far side, I knew they were having a race. I stood and stared.

Jack was on the outside and Blue was on the inside. I think it was the moment that they stretched their necks out and lengthened their stride that I began to worry, because, in fact, it did not look like they were playing—it looked like they cared. And unlike the training pen, which we sometimes put them in but was too small for them to get going, the arena was big enough for some speed but maybe small enough for trouble. A racetrack is a mile around. Not our arena. I looked toward the house. I didn’t know if I wanted Mom to see what was happening and come out and stop it, or if I wanted Dad to show up and yell at me. The best would be Danny. Danny should appear and treat me like a kid and help me prevent these horses from killing themselves.

Because they were going fast. Long, hard strides, digging deep into the footing, neck and neck, as they say at the racetrack. Blue was slightly ahead, but Jack did not want to give up. He even whinnied his high whinny. Their manes and forelocks flew, the sand rose around their bellies, and they ran. Their ears were pinned. I counted the number of circuits they made—one, two, three—and with each circuit, I thought of about a zillion different bad things that might happen. At one point, Blue’s foot slipped—he didn’t fall down, but he might have, so I imagined that for a while. Or he might have bumped Jack into the fence rail. Or he might have crossed Jack’s path and then they both could have gone down. Or there could be a hole or a depression in the sand that I didn’t know about—stumble, fall. What an idiot I was to have put them in here together. I shouted, “Hey, Blue! Hey, Jack! Slow down! Hey, fellas! Hey, Blue! Blue! How are you?”

And Blue’s ears flicked in my direction.

And Jack passed him.

Then they slowed down.

Then they trotted.

Then they tossed their heads and snorted.

Then Jack nipped at Blue and Blue nipped at Jack.

Then I saw how sweaty they were, and how hard they were breathing.

Then Blue turned and trotted over to me and Jack followed him.

They looked okay.

I said, “Thank you, Lord,” just the way Dad would have. And I meant it.

I got Blue’s halter off the gate and, since he had followed me, turned and put it on him right there, then I walked him around until he wasn’t panting any longer. Jack, in the meantime, was rolling in the sand—down, up, walk to another spot; down, up, walk to another spot. He seemed very proud of himself.

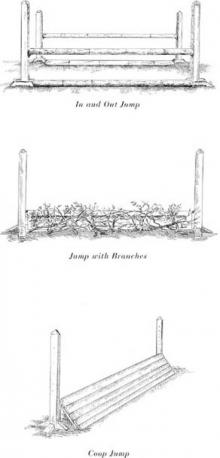

And me, well, my anxiety faded away and all I could think about was how beautiful and free they had looked, their tails streaming and their muscles shimmering. It was the way it had been earlier in the fall, when a trainer, Ralph Carmichael, was in town. He trained the horses to jump by having them gallop in pairs, or even in groups, down a jumping chute. The first time you saw it, it seemed like dangerous chaos, but then you realized that the horses not only enjoyed it, they were smart about it. Once we’d let Blue do it a few times, he knew more about jumping than I had been able to teach him.

When I came in for supper, which was macaroni and cheese and green beans, but with a peach pie, Mom and Dad were acting funny, so I knew something was going on. Then, when I was passing through the hall to go upstairs to the bathroom, I saw that there was an opened envelope on the telephone stand, and it was from the Wheatsheaf Ranch in Texas. It took about half a second for my heart to jump into my mouth, because that was the ranch wher

e Warn Matthews lived. Most people would say that Jack, who was almost two, belonged to Mr. Matthews. Most people would say that Jack’s dam, whom Dad had bought from a dealer in Oklahoma, had been stolen, so when she gave birth to a surprise foal out in our pasture, the foal belonged to Mr. Matthews, too, even though the mare colicked and died when he was a month old. Some people might say that although I adored Jack, I had to give him back. But Mr. Matthews didn’t think like that. He said that since we bought the mare in good faith, and since we took good care of her and her foal, we would share him “for now.” My problem was, I kept worrying about “later.” My hand just about grabbed the envelope on its own, but the letter wasn’t in the envelope. Mom or Dad probably had it in the kitchen. They were waiting for “the right moment.”

I went upstairs, but I was back downstairs in a hurry. When I sat down at the table, the letter, a typewritten page, was sitting at my plate. I picked it up. Even though Mr. Matthews had been plenty nice to me, that didn’t have to keep going. Sometimes people do things to you for your own good, and those things don’t feel good at all. The letter read:

Dear Abby, Mark, and Sarah—

It has been a busy year around Wheatsheaf, especially on the horse-racing side. You may or may not know that our three-year-old Yardstick, by Bold Ruler out of our homebred mare Hot Spell, has had quite an exciting season—fourth in the Kentucky Derby, second in the Preakness, then first in the Whitney and second to Buckpasser in the Travers. Of course, we would have preferred to win! But Yardstick has held up well, and should have a good year next year as a four-year-old. We have also been back and forth to Europe this year. We purchased an interest in a horse named Hill Rise, who looked as though he would be running in the Queen Elizabeth at Ascot and then the Arc. As it turned out, he didn’t go to France, but his win at Ascot was incredibly exciting, especially since he was bred in California.

All of this is by way of an apology for not having kept in touch with you concerning the yearling “Jack,” by Jaipur out of Alabama Lady. Yes, early in the summer, the Jockey Club informed us that after considerable debate, they have decided to allow Jack into the studbook. Although there is no definitive evidence that Jack is indeed Alabama Lady’s colt, or that your mare was Alabama Lady, the breeding and foaling dates, along with the circumstances of the theft and her appearance at By Golly Horse Sales, are sufficiently compelling to tip the scales in our favor. My guess is that they went back and forth about this matter for a good long while, but whatever happened, they have now decided to accept him. Being a gelding may have helped him, because they only have to let him race, and don’t have to worry about offspring. Anyway, we must make up our minds what to do next.

Normally, a Thoroughbred born in January, as Jack was, goes into training in September of his second year—which would have been this past September—so that he can have a couple of races as a two-year-old. Around Wheatsheaf, we don’t press the two-year-olds very hard, but we have found that the ones who wait to run, for whatever reasons of health or circumstances, are harder to handle and are less likely to do well. My own theory is that three-year-olds are like kids in junior high—sassier and more rebellious—so you want your horses to have learned their job when they are still willing. Since we have our own training facility here, we can take it horse by horse, start them, and go on with them as we wish, and then we normally ship them to Kentucky and Arkansas to begin their racing careers. But I don’t see how this will work with Jack. For one thing, he is not used to Texas weather, especially the humidity, and for another, my son Barry, whom you have not met, has gotten to know a fellow in your neighborhood who runs a well-respected training facility pretty much down the road from you called Vista del Canada. The man’s name is Roscoe Pelham, he’s an experienced horseman, and he’d like to have Jack over there.

The only other question that remains is what Jack’s registered name will be. Some racehorse names are pretty ridiculous—I’m proud of “Yardstick” in a way, because lots of Bold Ruler horses have what I consider prideful names, but “Yappy” and “Buckaroo Banana” just seem a little silly to me. So we need to start thinking of something.

I hope this is good news for you, and that you and your horses, and Jack, of course, are all well and happy. Maybe sometime after the racing season, you folks can come down to Wheatsheaf for a little visit.

I look forward to hearing from you.

Warn Matthews

Mom said, “Doesn’t Jake Morrisson shoe horses over at that place? Maybe Danny’s actually been there.”

Dad said, “You’re thinking of Laguna Seca. Vista del Canada is the private place—don’t know a thing about it, except that it is supposed to be very grand.”

I said, “Jane might know some of those people. She talked about them once.” Jane was the manager of a big stable on the coast where I rode in shows.

Dad said, “Those aren’t the same ones, I’m sure.” What he meant was, those aren’t the people who tried to cheat us out of five thousand dollars right around the time that Mr. Matthews showed up and saved the day. But he looked worried, because what was the difference between one horse-racing gambler and another, really? I mean, he liked Mr. Matthews because he was a rancher, and they could talk cattle and cow horses. Or I thought that was why he looked worried, until he said, “I wonder what it costs.”

Mom said, “I guess we’ll find out.”

Dad said, “We need to find out before we take the horse over there, is what I think.”

I thought about my bank account—a hundred and six dollars. I wondered how long that would last, even if Mr. Matthews was splitting it with us. Dad said, “I’ll write him back, and we’ll pray on it.” I saw that he was pretty reluctant to open the Bible and see what Scripture advised, and I didn’t blame him.

Even though I had to get up early to get to the school bus, I couldn’t help lying awake, wondering about sending Jack to a place that was “down the road,” much less to Texas. I had pretty much forgotten about the fact that Mr. Matthews might want to do something with Jack—we hadn’t heard from him all summer, and what with riding, and training Blue, and trying to figure out high school, I hadn’t thought about the Jockey Club in months. Well, wasn’t this a good thing? Yes, Jack was the son of Jaipur and the grandson of Nasrullah and Determine. But I sort of hoped that Dad would decide that it was too much money. (And how much would that be? The stables where the horse shows were, where Sophia Rosebury kept her horses, and where Blue had come from, charged a hundred dollars every month just for board, and that didn’t include any training—board and breaking and training could be twice that.) Maybe Jack could stay home.

I rolled over, and of course what happens when you roll over is that you get another bad thought. Mr. Matthews was nice enough now, but if we decided that we didn’t want Jack to go to Vista del Canada, maybe he could just say, “Okay, Texas it is,” and Jack would have to go there. It was about at this point that I decided that I would write Mr. Matthews myself, and suggest that we keep Jack at home and Jem Jarrow could start him. Yes, that was a good idea, and I would think about the name later. I fell asleep. Jem Jarrow wore cowboy boots and worked at his brother’s ranch, but he could train any horse to do anything.

That was Wednesday. Friday, we had a surprise. It was a pleasant surprise, but it was definitely a surprise. Dad and I were riding Mr. Tacker’s five-year-old quarter horse gelding, Marcus, and our beautiful paint mare, Oh My, in the arena when a truck and trailer pulled up to the gate, and Danny got out of the passenger’s side, opened the gate, let the rig through, and closed the gate. It was a nice two-horse trailer and a new truck—newer than ours. When it pulled up to the parking area beside the barn, a guy got out. He looked about Danny’s age. He was wearing the usual stuff—jeans, cowboy hat, jean jacket. He and Danny came over to the fence, and he took off his hat. His hair popped up like it was made of springs. He dipped his head to us, and Danny said, “Dad, this is Jerry Gardino. Jerry, this is my dad, Mark Lovitt, and my s

ister, Abby. Jerry’s looking for a place to keep his horse for a couple of months, and I knew you had room. There’s nothing at Marble Ranch at the moment.” Marble Ranch was the ranch where Danny worked and lived. Then, as if reading Dad’s mind, Danny said, “Jerry knows that you charge seventy-five dollars per month with him supplying oats or corn.”

Dad relaxed at once, and said, “The more the merrier.”

Jerry Gardino gave us a smile, and it was a very big smile. It made you smile right back.

He said, “Thanks, Mr. Lovitt. I really appreciate this. The season’s over, and Beebop needs a little time off. Danny says he’ll get great care, and this place looks perfect. There’s a spot up where I go to school, but no grass, and not much turnout. Hate to do that to a horse.”

I dismounted, and Jerry cemented his good impression by saying, “That one’s a beauty.”

Dad leaned over and gave Oh My a pat and said, “Well, the black-and-white overo paint is fairly unusual, for sure, but look at this.” I turned Oh My around so Jerry could see the question mark on her left side. He said, “Oh my.” They always did.

Dad said, “What kind of horse do you have?”

“Oh, Beebop is a little bit of everything—Thoroughbred mixed with quarter horse mixed with sixteen other varieties maybe. Some mustang in there for sure. He’s a bucking horse. I take him around to rodeos, and mostly he gets out from under ’em.”

Danny said, “You should see the pictures.”

The horse, when we unloaded him, was nice enough—a liver chestnut with a friendly eye, no white on him, and of medium height and build—just the sort of horse that a judge wouldn’t look at twice. We put him in a stall with a nice pile of hay for the night, and Danny said he would come over with Jerry the next day and introduce him to the geldings. Then Mom came out and invited the two of them for supper, and by the fact that we were having fried chicken and mashed potatoes and gravy, it was clear that she had known about this all along.

The Georges and the Jewels

The Georges and the Jewels Pie in the Sky: Book Four of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch

Pie in the Sky: Book Four of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch Duplicate Keys

Duplicate Keys Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens Good Faith

Good Faith Private Life

Private Life A Thousand Acres: A Novel

A Thousand Acres: A Novel The Greenlanders

The Greenlanders Ten Days in the Hills

Ten Days in the Hills Gee Whiz: Book Five of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch

Gee Whiz: Book Five of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch A Thousand Acres

A Thousand Acres The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton

The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton Ordinary Love and Good Will

Ordinary Love and Good Will Taking the Reins (An Ellen & Ned Book)

Taking the Reins (An Ellen & Ned Book) The Man Who Invented the Computer

The Man Who Invented the Computer Horse Heaven

Horse Heaven The Age of Grief

The Age of Grief Riding Lessons

Riding Lessons Perestroika in Paris

Perestroika in Paris A Good Horse: Book Two of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch

A Good Horse: Book Two of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch Saddles & Secrets (An Ellen & Ned Book)

Saddles & Secrets (An Ellen & Ned Book) Some Luck: A Novel

Some Luck: A Novel Champion Horse

Champion Horse Some Luck

Some Luck Gee Whiz

Gee Whiz Barn Blind

Barn Blind A Thousand Acres (1992 Pulitzer Prize)

A Thousand Acres (1992 Pulitzer Prize) Pie in the Sky

Pie in the Sky True Blue

True Blue A Thousand Acres_A Novel

A Thousand Acres_A Novel A Good Horse

A Good Horse