- Home

- Jane Smiley

True Blue Page 14

True Blue Read online

Page 14

They came to the end of the arena and went past the oak tree there, and just then, Rusty leapt out of the grass, and Blue reared, turned, and bolted in my direction. Danny grabbed the horn of the saddle and his hat flew off. He lost a stirrup, but he didn’t fall off. But even when he had the reins and was with the horse again, he didn’t make him stop, as I would have done. He turned him back into his spiral, this time at a gallop, then at a canter, and when they got to the center, he trotted him for two steps and went off on the other lead. They did the spiral at the canter twice, not as smoothly as they had done it at the trot, but pretty well, considering that Danny directed the spiral so that its outer rings got closer and closer to where Rusty had scared Blue.

I shouted, “Rusty!” but Danny waved his hand at me. I realized that he wanted Rusty to be there—he wanted Blue to see what had scared him and understand it. I crossed the arena, avoided Danny and Blue, and picked up Danny’s hat. Finally, they came over to me, and Danny let Blue halt. Blue was heaving. Danny was breathing pretty hard, too.

I said, “That was good riding.”

Danny said, “Yup. It was.” He took his hat and straightened the brim, then put it on. He glanced up the hill. Daddy was still inspecting the fence posts—he was practically to the end of the fence and out of sight by this time. I could just see Amazon’s tail and the roundness of her haunch.

We didn’t say anything for a moment, and then I said, “He did that with Daddy, just ran. Almost ran over me, too.”

“What did he see?”

“A ghost.”

“Oh, you mean the ghost of a big brown dog jumping out of the grass?”

“No. I don’t mean that.”

Danny blew out a little air and said, “Well, this one I have to give him, because he was concentrating on what I was asking him to do, and then there was the dog, who I think was chasing a rabbit, so sometimes there is a reason.”

“But it seems like he’s always got a reason, or at least an excuse.”

“What did he do before?”

“No one knows. He went on trail rides. Everything about him and his owner is a mystery.” I thought of Alexis saying, “Mmysstery!” as if mysteries were fun, and smiled. Then I said, “Who did you ride today?”

“This one. Happy. Just the two.”

“How did you like Happy?” I said this innocently, as if I didn’t know the answer, which was that Danny and Happy were made for each other.

Danny said, “She’s a pretty nice horse.”

At school, when someone really loves something, it’s great, or it’s really cool, big smile, wow! When Mom really loves something, she just says, “I love that.” I think maybe one time I heard Daddy say that so-and-so was “a pretty nice horse” and that horse was Lester, his favorite ever. From someone like Danny or Daddy, “a pretty nice horse” was the best compliment of all. But I didn’t say anything. I nodded, and then changed the subject. “So, what are you doing tonight?”

He pushed his hat back. “I don’t know. Why?”

“I don’t believe you.”

“I might go to a movie.”

“Danny, the cat is out of the bag.”

“Which cat?”

“You know!”

He pulled on the lobe of his ear, then turned Blue away from me. Yes, they were sweaty and had to walk. I shouted, “Just tell me what movie!”

Danny shouted, “Lord Love a Duck!”

This was a movie no one had talked about in school, not even Alexis and Barbie, so I figured it was a strange one. Probably Leah’s choice.

By the time I was finished helping Mom as best I could with the cooking, Danny was gone. Mom seemed in a good mood, though. Daddy came down from the fence line and rode Jefferson before feeding the horses and coming in for dinner. No one said anything about Danny, and the rain started again while we were eating. Before bedtime, I made myself read Le Petit Prince in French until I fell asleep. It worked.

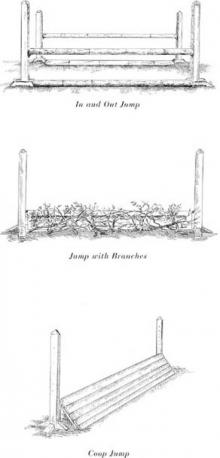

Mounting Block

Stall Door

Chapter 16

GETTING A LOT OF FOOD TO CHURCH WAS ALWAYS TIME-CONSUMING, and getting it there in the rain was really hard—you did not want a lemon meringue pie to be rained on. We started out the door about ten minutes before we usually did, but still we were heading through our gate about five minutes later. This was why, as Mom and Daddy were sitting in the car and I was closing the gate while trying to keep my cast dry, we happened to see Danny going past in his car, on his way to the Jordan ranch. He waved. I waved. I couldn’t see whether Daddy, who was driving, or Mom, who was sitting in the backseat guarding the pies, waved. I opened the door and got in, not forgetting to pick up the two dishes I had to carry in my lap, the salad and the beets. I hated beets—I could smell them through the waxed paper that Mom had rubber-banded around the bowl.

As we pulled away, Mom said, “I was so silly to make these pies. I just—”

Daddy said, “They’re fine, Sarah,” in a way that suggested that seeing Danny drive away from church, even though we knew he didn’t go to church, was especially bad. I glanced at her. Her lips said, “Shh,” but she made no noise. We drove to the church in silence, which was fine with me, because those beets and that salad occupied all my attention. When we got to church, Brother Abner and Sister Larkin and Carlie and Erica Hollingsworth were waiting by the curb to take the dishes. The rain was even worse in town, but Brother Abner walked next to each pie, holding his umbrella over it until it got through the door. Once all the food was taken in, Mom and I got out, and Daddy went to park the car.

Mom said, “Wooo. Ice cold in there.”

“You mean in the car?”

She nodded. “Danny working on Sunday.”

“Maybe he’s not working.”

“Wouldn’t that be worse?”

I said, “I don’t know what would be worse, Mom.”

She nodded.

Daddy was the last person in the door, and he had to take off his raincoat and stomp the water out of his boots. By the time he sat down, it was clear that the five empty chairs in the second row that had been empty for two weeks now, the Greeleys’ chairs, were not going to be filled. I could hear the sisters all around clucking, and there was some head-shaking, too, but no one said anything, and we sang a few songs. Carlie’s dad started these, and they were good ones: “How Can I Keep from Singing?” and “Gather Them In” and “Rock of Ages.” After we sang all the verses to these, then we did our favorite, which was “Amazing Grace,” all the way through, seven verses. And after that, all the brothers and sisters sighed and smiled, and Brother Abner got up and read his text, which was, “ ‘Then the cupbearer and the baker for the king of Egypt, who were confined in jail, both had a dream the same night, each man with his own dream and each dream with its own interpretation.’ ” This led Brother Abner to talk about a dream that he had had, that he was walking down the road, and a girl came up to him, and he realized that the girl was his own mother. The girl said that she was lost, and Brother Abner took her hand and walked with her down the road, the whole time asking himself whether he should tell her that he, an old man, was her son. He didn’t know if this would make her sad or happy, and at this point the dream ended.

Everyone was quiet, and then Carlie’s dad stood up and read a selection about Jesus and the loaves and the fishes, which we had heard many times. He finished talking, and then Brother Ezra Brooks, who had never said anything that I could remember, jumped to his feet and said, “ ‘And it shall come to pass in the last days, saith God, I will pour out of my Spirit upon all flesh: and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, and your young men shall see visions, and your old men shall dream dreams!’ ” Sister Brooks turned and stared at him, then took his hand and got him to sit down again. Everyone else acted like he hadn’t spoken. Carlie’s dad stood up and looked around, then started another hymn, which was “Balm in Gilead.” Then we separated, and the kids went to study the Bible with Sister Larkin, and the parents studied the Bible, too. Sister B

rooks quietly slipped out with Brother Ezra.

Maybe it was a Sunday like any other, but it didn’t seem to be. As I passed slowly around the table where Mom and Mrs. Larkin had set out the food, putting down my plate and steadying it with the fingers of my left hand, while dishing some stew and rice onto it with my right, and then salad and bread and the other things, I heard everyone talking in low voices about Brother Abner’s dream. “Just the saddest thing,” said Sister Larkin, and Mom asked why, and Sister Lodge said, “To come to your own mother as an old man? I had tears.” And Sister Ethelyn Larrabee, who had never married, said, “I imagined that he was talking about meeting her in heaven, and he only thought he was an old man. Really, he appeared to her as she appeared to him, a golden youth.”

But Sister Marian Larrabee, who had also never married, said, “The first thing I thought was that she was going to forgive his sins and ask him to forgive hers.”

Sister Lodge shook her head. “She was lost. That was the saddest part for me.”

And Mom said, “Who isn’t, really?”

But no one answered her.

I wondered if any particular sins committed by Brother Abner were known to the ladies, or if they were just talking in general. Daddy already had his food, and Mom was walking toward where he was sitting. I had set my plate next to the creamed corn and picked up the spoon when I heard his voice rise. He said, “It is the sins of the fathers that are visited on the sons, and this is how it happens.” Mom stopped in her tracks.

Carlie’s dad exclaimed, “I told you Thursday that it’s not our business, and I still think that.”

Brother Abner said, “Each man with his own dream and each dream with its own interpretation.”

Daddy snapped, “We’re not talking about dreams!”

Brother Abner pursed his lips, but said no more.

Brother Brooks, who had not left with Sister Brooks and Ezra, said, “Maybe we should say what we are talking about, then.”

Daddy said, in his firm voice, “We are talking about rules, and more than that, we are talking about sparing the rod and spoiling the child. When you are young, these things seem much more difficult than they are, but it’s quite simple, really. The children are wild and disruptive. If we don’t speak up, if we just stand back and let it happen, then we are implicated. We owe it to the children more than anyone else.” I realized he was talking about the Greeleys.

Brother Abner said, “To make sure they get whipped, you mean?”

“If that’s what they need,” said Daddy. But then he looked around and saw that everyone was staring. He said, “Everyone in this room’s been whipped and more than once.”

“That’s right,” said Brother Abner. “I was whipped at home and I was whipped at school. What I think now is that those whippings raised the spirit of rebellion in me. Made salvation take longer, you ask me.”

Now Sister Brooks came back in with Ezra, and they went to their places and sat down. Ezra put his hands between his knees and looked at the floor.

Sister Larkin began thumbing through her Bible.

Daddy said, “If the devil is in there, then the devil has to be driven out.”

Sister Marian and Sister Ethelyn muttered that this was true, though regrettable. I looked at Mom. She was sitting near Daddy, holding her plate on her knees. She was looking at the floor.

Brother Brooks said, “I’m not sure it’s as simple as all that—”

I thought they could have asked me. Over the past couple of years, Carlie and I had spent more time alone with the Greeley kids than any of them had. I looked over at Carlie, but once again, she had her nose in a book. I watched her. She didn’t turn the page, but she wouldn’t look at me. Erica, who was ten, was hiding her face in her mother’s side. Mrs. Hollingsworth was patting her on the leg. I saw that no one but Daddy wanted to have this argument. Finally, Mr. Hollingsworth said, “Brother Lovitt, we may all have our opinions about each other, but unless we maintain a spirit of forgiveness, the congregation will split.”

“What’s right is right,” said Daddy. “I cannot sit here in good conscience and allow wrong to persist.”

At last, Sister Larkin spoke up. She said, “The fact is, they’ve been driven off already. Rhoda Greeley told me last week that they don’t expect to return to the fold.”

“They were not ‘driven off,’ ” said Daddy. “No one spoke a word of blame the day that child ran away. Not one word of blame.”

Except, of course, they had blamed me—not angrily, but sorrowfully.

“Looks were enough,” said Sister Larkin. “They knew.”

Sister Ethelyn said, “It was understandable that some of us felt that our patience had been tested. But if we cannot welcome the testing of our patience, then we are weak vessels indeed. That’s what I think.”

Sister Brooks said, “The poor child might have been killed.”

“Exactly,” said Daddy. “Exactly.”

I couldn’t tell what he felt Sister Brooks was agreeing with. I thought she was carefully reminding everyone that if I had been paying attention, none of this would have happened. I felt my face get hot and I set my fork on my plate. My feeling got stronger when I saw her glance flick toward me, just for the briefest second. I wasn’t even sure that she realized that she looked at me. Mr. and Mrs. Brooks both took deep breaths at the same time, and then Brother Hazen, who usually had a lot to say but hadn’t said anything so far, turned to Daddy and said, “We’ve spoken of this over and over, Brother Lovitt, most recently Thursday afternoon. Every congregation has to welcome younger members. You, yourself, don’t see this, because you are young, but we see it.”

Mom set her plate on the floor and put her hands on her knees.

Daddy said, “What happens if the children don’t learn to submit? What happens if the children are never taught to submit? ‘God is opposed to the proud, but gives grace to the humble. Submit therefore to God. Resist the devil and he will flee from you.’ That verse seems clear to me.” Now he looked around. Then he said, “Tell me I’m wrong. Instruct me and I will listen.”

Everyone went quiet. Carlie closed her book, but she didn’t look up, and I had the feeling you have when you walk into study hall at school, and you know they’ve been talking about you. You might be wearing the wrong shirt, or there’s something on the hem of your skirt. One time, Kyle Gonzalez walked all around school for three periods before Richie Russo told him that there was a piece of paper on his back with the words SO SUE ME printed on it. “So sue me” was something Kyle had said to Johnnie Rogers by the lockers one morning. I never knew why.

Mr. Hazen spoke up and did the thing we always did. He said, “I suggest we turn this situation over to the Lord, asking for guidance on how we proceed with this matter.”

Sister Larkin then said, “I don’t see what good guidance for us is. They aren’t coming back.”

But Brother Hazen bent his head and said, “Lord, in this situation concerning the Greeleys, we seek your divine inspiration. In Jesus’s name we ask, amen.”

In about another minute, we all picked up our forks and started eating again.

It didn’t take as long to put the dishes in the car when we were ready to go home. Some of the older sisters and Brother Abner had divvied up the leftovers, so the dishes were empty and we put them in the trunk. This time I got in the backseat, and Mom got in the passenger seat. As we pulled away from the curb and headed toward the place where the parking lot exited onto the street, it was as if the hours between dinner and the end of the second service hadn’t even happened, because Daddy said, “I know you agree with me, Sarah.”

Mom said, “About what?”

“About sparing the rod.”

We drove. The windshield wipers swished and the rain, which was still pretty heavy, flew to either side. I wished Daddy would talk about the rain—would there be an inch in the rain gauge at home, or two?

Finally, Mom said, “You know I wasn’t whipped and was hardly spanked

when I was growing up. If my mom slapped me once on my bottom with an open hand, I’d be surprised. And I never saw her spank my sisters, either.”

Daddy turned and smiled at her. “Because you girls were always good and never prideful.”

Mom ducked her head.

I said, “You never spanked me, did you?”

Daddy glanced around, then looked back at the street. He said, “I smacked you on your diaper when you were two and a half once. You were running into the road. I wanted you to remember never to go there. But you were like your mom.”

And who wasn’t, I thought.

After a minute, Daddy said, in that voice parents use when they are telling you about when they were kids, “Your grandpa whipped us boys every week, whether we needed it or not. That’s what he always said. But he knew we needed it. If he didn’t know everything we’d done, well, he knew we’d done something.”

The Georges and the Jewels

The Georges and the Jewels Pie in the Sky: Book Four of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch

Pie in the Sky: Book Four of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch Duplicate Keys

Duplicate Keys Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens Good Faith

Good Faith Private Life

Private Life A Thousand Acres: A Novel

A Thousand Acres: A Novel The Greenlanders

The Greenlanders Ten Days in the Hills

Ten Days in the Hills Gee Whiz: Book Five of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch

Gee Whiz: Book Five of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch A Thousand Acres

A Thousand Acres The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton

The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton Ordinary Love and Good Will

Ordinary Love and Good Will Taking the Reins (An Ellen & Ned Book)

Taking the Reins (An Ellen & Ned Book) The Man Who Invented the Computer

The Man Who Invented the Computer Horse Heaven

Horse Heaven The Age of Grief

The Age of Grief Riding Lessons

Riding Lessons Perestroika in Paris

Perestroika in Paris A Good Horse: Book Two of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch

A Good Horse: Book Two of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch Saddles & Secrets (An Ellen & Ned Book)

Saddles & Secrets (An Ellen & Ned Book) Some Luck: A Novel

Some Luck: A Novel Champion Horse

Champion Horse Some Luck

Some Luck Gee Whiz

Gee Whiz Barn Blind

Barn Blind A Thousand Acres (1992 Pulitzer Prize)

A Thousand Acres (1992 Pulitzer Prize) Pie in the Sky

Pie in the Sky True Blue

True Blue A Thousand Acres_A Novel

A Thousand Acres_A Novel A Good Horse

A Good Horse