- Home

- Jane Smiley

A Thousand Acres (1992 Pulitzer Prize) Page 15

A Thousand Acres (1992 Pulitzer Prize) Read online

Page 15

He smiled warmly at me, then wrapped his hand around my arm, pulled me toward him, and kissed me. It was a strange sensation, a clumsy stumbling falling being caught, the broad, sunlit world narrowing to the dark focus of his cushiony lips on mine. It scared me to death, but still I discovered how much I had been waiting for it.

OUT WEST, EVEN AS CLose as Nebraska and South Dakota, there were farms that dwarfed my father's in size, thousands of acres of wheat or pastureland rolling to the horizon, and all owned by one man. In California there were unbroken rows of tomatoes or carrots or broccoli miles long, farmed by corporations. In Zebulon County, though, my father's thousand acres made him one of the biggest landowners. It was not that the farmers around us were unambitious.

Perhaps there were those who dreamed of owning whole townships, even the whole county, but the history of Zebulon County was not the history of wealthy investment, but of poor people who got lucky, who were sold a bill of goods by speculators and discovered they had received a gift of riches beyond the speculators' wildest lies, land whose fertility surpassed hope.

For millennia, water lay over the land. Untold generations of water plants, birds, animals, insects, lived, shed bits of themselves, and died. I used to like to imagine how it all drifted down, lazily, in the warm, soupy water-leaves, seeds, feathers, scales, flesh, bones, petals, pollen-then mixed with the saturated soil below and became, itself soil. I used to like to imagine the millions of birds darkening the sunset, settling the sloughs for a night, or a breeding season, the riot of their cries and chirps, the rushing hough-shhh of twice millions of wings, the swish of their twiglike legs or paddling feet in the water, sounds barely audible until amplilied by millions. And the sloughs would be teeming with fish: shiners, suckers, pumpkinseeds, sunfish, minnows, nothing special, but millions or billions of them.

I liked to imagine them because they were the soil, and the soil was the treasure, thicker, richer, more alive with a past and future abundance of life than any soil anywhere.

Once revealed by those precious tile lines, the soil yielded a treasure of schemes and plots, as well. Each acre was something to covet, something hard to get that enough of could not be gotten Any field or farm was the emblem of some historic passion. On the way to Cabot or Pike or Henry Grove, my father would tell us who owned what indistinguishable flat black acreage, how he had gotten it, what he had done, and should have done, with it, who got it after him and by what tricks or betrayals. Every story, when we were children, revealed a lesson-"work hard" (the pioneers had no machines to dig their drainage lines or plant their crops), or "respect your elders" (an old man had no heirs, and left the farm to the neighbor kid who had cheerfully and obediently worked for him), or "don't tell your neighbors your business," or "luck is something you make for yourself." The story of how my father and his father came to possess a thousand contiguous acres taught us all these lessons, and though we didn't hear it often, we remembered it perfectly. It was easily told-Sam and John and later my father had saved their money and kept their eyes open, and when their neighbors had no money, they had some, and bought what their neighbors couldn't keep. Our ownership spread slowly over the landscape, but it spread as inevitably as ink along the threads of a linen napkin, as inevitably and, we were led to know, as ineradicably.

It was a satisfying story.

There were, of course, details to mull over but not to speak about.

One of these was my grandmother Edith, daughter of Sam, who married John when she was sixteen and he was thirty-three. The marriage consolidated Sam's hundred and sixty acres with John's eighty. My father was born when Edith was eighteen, and after him two girls, Martha and Louise, who died in the flu epidemic of 1917.

Edith was reputed to be a silent woman, who died herself in 1938 at forty-three years old. My grandfather, a youthful fifty-nine by then, outlived her by eight more years. I used to wonder what she thought of him, if her reputed silence wasn't due to temperament at all, but due to fear. She was surrounded by men she had known all her life, by the great plate of land they cherished. She didn't drive a car. Possibly she had no money of her own. That detail went unrevealed by the stories.

Land was purchased around the time she died. In fact, land was bought twice, first the hundred and eighty acres in the southwest corner, then, some months later, but also in 1938, the two hundred and twenty acres east of that. My father always said that frugality was the key-his father had managed to save money on machinery, and when the acreage came on the market, they could afford to pay a dollar more per acre for it. Some time later, I found that this was only true of the first piece. The story of the second parcel was more complicated, less clearly imparting one of those simple lessons. The farmer was Mel Scott, who was a cousin by marriage to the Stanleys.

He wasn't known to be much of a farmer, but he had good land, and a reasonable acreage for those times. The trouble was, he refused to go to his cousins for help or advice, because he didn't want them to know how badly he was doing. He forbade his wife to divulge anything to her family, which eventually meant not seeing them, as her clothing and the children's clothing fell to rags. No going to church, no invitations made or accepted. Scott, meanwhile, sought advice of my grandfather, and money of my father, his neighbors, which was shameful enough but nothing compared to the humiliation of standing before Newt Stanley or his wife's other wealthy, powerful, and outspoken cousins, who had not resisted the marriage, but had mocked it a little. He didn't borrow much money from my father; there wasn't much to borrow.

Then it came time to pay the taxes, and Mel Scott came over late one November night and knocked on the beveled glass front door of the big Sears Chelsea. I imagine it as one of those winter nights on the plains, clear and black, when space itself seems to touch the ground with a universal chill, and a farmer who has walked a half mile over the fields, despairing but fearful, too, and full of doubts, arrives at the dark house of his neighbor. He knocks lightly on the door, almost, at first, wishing not to be heard, then again, with more pride (it's no sin to be struggling-everyone is struggling). No one answers, there are no lights, only the rattle of feed pans from the hogs and cattle in the barn. So he turns, and walks to the edge of the porch, and maybe thinks about just going home. But it is so cold, getting colder, and the half mile expands to a marvelous distance. Surely he will die before he covers it again on foot. So he knocks again, more loudly, and shouts, and my father, who sleeps in one of the front bedrooms, awakens from his hardworking slumbers and comes down. My grandfather gets up. A light is turned on, an agreement is made. My grandfather will pay the taxes if Mel Scott will sign over his land. He can then farm it on shares and buy it back when commodities prices go up. The taxes aren't much. Twenty years before, a man could have paid them without thinking about it. Those times are sure to return again.

They shake hands all around, and, a little warmed by the last coals in the kitchen range, Mel sets out for home. He is saved, hopefulhe has gotten what he wants. But getting what he wants removes the veil of panic that has kept him stumbling forward a single step at a time for these last years, and reveals to him that he no longer wants what he wanted before, what he thought he always wanted.

Time, Mel thinks, to sell up, to move to the Twin Cities and get a job.

How could they make it through the winter, anyway? When he gets home, he is ecstatic with the cold, the crystalline air, the high pressure that hums over the whole defenseless breast of the continent, and ecstatic, too, with a hope that turns failure into success, plans for a trip, a new life, city time. The next day he signed the farm over to my father and grandfather, and he borrowed a little more money to cover the expenses of moving. My father and grandfather took over the land and the few crops still standing in the fields. They knocked down the buildings when I was a teenager, and after that there were only traces, the shadowy depression of the pond in the fields and the circle of the old well, filled in, to show that lives had been lived there.

The Stanley brothers wer

e furious. Said my father had engineered it all, to get a whole farm for the taxes and something over, a fee, you might call it, for the disposal of the encumbering family. It was a transaction my father never spoke of knowledge that came to me through gossip thirty years later. When I used to sift through it, I didn't see how it especially redounded to my father's or grandfather's discredit. A land deal was a land deal, and few were neighborly. But I now wonder if there was an element of shame to Daddy's refusal ever to speak of it. I wonder if it had really landed in his lap, or if there were moments of planning, of manipulation and using a man's incompetence and poverty against him that soured the whole transaction.

On the other hand, one of my father's favorite remarks about things in general was, "Less said about that, the better."

The death of my mother coincided with the departure of the Ericson family, and our purchase of that farm. In fact, I remember that after my mother's funeral, after the service and the burial and the buffet that Mary Livingstone and Elizabeth Ericson served at our house for the mourners, I followed Mrs. Ericson across the road, carrying some empty serving dishes, and after I put them beside the sink, I walked into the living room. The parrot cage was covered, and the dogs were outside.

The rest of the family was still at my house, and the Ericson house, the house I later came to call my own, was the one that was still as death. I pushed aside some books and newspapers, and sat on the sofa.

The parrot wasn't entirely silent beneath his covering. I could hear him scrape the perch with his talons and mutter to himself. A cat walked through the room and marked two chairs by rubbing his arched back against them. I liked the silence and the sense of companionship I felt from the animals, and I experienced, for the first conscious time, the peaceful selfregard of early grief when the fact that you are still alive and functioning is so strangely similar to your previous life that you think you are okay. It is in that state of mind that people answer when you see them at funerals, and ask how they are doing. They say, "I'm fine. I'm okay, really," and they really mean, I'm not unrecognizable to myself. Anyway. In the midst of this familiar silence and comfort, Mrs. Ericson came into the room, surveyed me from the doorway, then sat down beside me. She was wearing an apron with a red and white checked dish towel sewn to it, and she wiped her hands on the towel as she sat down. She was not one to mince words, and she said, "Ginny, sweetheart, I have some more bad news for you. Cal and I have sold the farm to your father, and we're moving back to Chicago. We just can't make it here. We don't know enough about farming."

I looked at her looking at me, and ii, retrospect, I think that I did feel everything gentle and fun and happy draining away around me.

I think that though I was only fourteen and not accustomed to judging my life or my father, or demanding more of our world than it offered of itself I knew exactly what was to come, how unrelenting it would be, the working round of the seasons, the isolation, the responsibility for Caroline, who was only six. I didn't cry then. I had been crying all morning and I was at the end of tears. I said, "I wish you would take me with you," and Mrs. Ericson said, "I wish we could," and then she cried, and then some people came in the back door with more plates, and she got up from the couch. I said, "Can you uncover the parrot's cage?" She nodded. When she left the room, I sat staring at the green back of the parrot and his preternaturally limber neck.

His head worked up and down and swiveled around like an oiled machine, then, finally, carefully, using his beak, he rotated on his perch and cocked his head to eyeball me. I said, "Hi, Magellan." He said, "Sit up! Reach for it!" And I laughed.

Three weeks later, the Ericsons were gone, and my father carefully boarded the farmhouse against the wind and dust. Five years later, when he took off the boards and Ty and I moved in, I had stopped thinking about the past-my mother, the Ericsons, my childhood.

I loved the house the way you would any new house, because it is populated by your future, the family of children who will fill it with noise and chaos and satisfying busy pleasures.

Nothing about the death of my mother stopped time for my father, prevented him from reckoning his assets and liabilities and spreading himself more widely over the landscape. No aspect of his plans was undermined, put off questioned. How many thousands of times have I seen him in the fields, driving the tractor or the combine, steadily, with certainty, from one end of the field to another. How many thousands of times has this sight aroused in me a distant, amused affection for my father, a feeling of forgiveness when I hadn't consciously been harboring any annoyance. It is tempting to feel, at those moments, that what is, is, and what is, is fine. At those moments your own spirit is quiet, and that quiet seems achievable by will.

But if I look past the buzzing machine monotonously unzipping the crusted soil, at the field itself and the fields around it, I remember that the seemingly stationary fields are always flowing toward one farmer and away from another. The lesson my father might say they prove is that a man gets what he deserves by creating his own good luck.

THE MoNoPoLY GAME ENDED with the news that Caroline and Frank had gotten married in a civil ceremony in Des Moines. The paragraph, in the Pike Journal Weekly that was published the twenty-second of June, said, "Miss Caroline Cook, daughter of Laurence Cook, Route 2, Cabot, and the late Ann Rose Amundson Cook, was married to Francis Rasmussen of Des Moines, on Thursday, June 14. The ceremony took place at the Renwick Hotel in New York City, New York. Mr. Rasmussen's parents are Roger and Jane Rasmussen, of St. Cloud, Minnesota. Congratulations!

The bride, a lawyer in Des Moines, will continue to use her maiden name-more girls are, these days!"

We might not even have seen it if Rose hadn't taken the girls into Pike to buy some sneakers at the dime store and picked the newly printedJournal Weekly from a stack on the counter. Dorothy, checking her purchases, said, "I see your sister got married," and Rose, for whom this was the freshest possible news, said, "Yes, it was a very small ceremony.

Dorothy said, "Those are nice, too."

Rose followed the girls to the car, gripping the paper and reading the item over and over. In the car, Linda said, "Why weren't we invited to Aunt Caroline's wedding?"

Rose said, "I don't know. Maybe she's mad at us."

Rose was beyond mad and well into beside herselfwhen she banged into my kitchen and slapped the paper, open to the paragraph, down on the counter in front of me. I was peeling potatoes for potato salad.

I read the paragraph.

Rose said, "She didn't mention a word about this when you talked to her Friday, did she?"

"No."

"Or Tuesday?"

"Well, no. She had other things on hen" "Don't say that! Don't come up with an excuse! Just look at it, and admit what it shows!"

"I don't quite understand. I mean, this wedding has already taken place?" I glanced at the publication date, today, then at the paragraph again. "Don't you think there's a mistake?"

"Do you want to call Mary Lou Humboldt and ask her about it?

Then next week, she can put in a little item about how the Cook sisters don't seem to know what's going on with Caroline."

"Maybe we should call Caroline.

"For what? This is for us! This is how she's letting us know."

Then she told me what she'd said to Dorothy at the dime store.

"The thing is just to take it in stride, to not even be surprised. And I'm going to send her a present! An expensive present, with just a little card saying, 'From Rose and Pete and the girls, thinking of you both."" I laughed, but when Rose left, I realized that I felt the insult physically, an internal injury. It reminded me that she wasn't in the habit of sending birthday cards, or calling to chat, that when she used to come home to take care of Daddy, she didn't bother to walk down the road to say "Hi" unless she needed something. It reminded me of how she was, a way that Rose found annoying and I usually tried to accept. It reminded me that we could have taught her better manners, had we known ourselves that good mann

ers were more than yessir, no sir, please, thank you, and you're welcome.

The men didn't agree that Caroline had done anything especially insulting. The wedding, the marriage, was her business and Frank's, and they probably didn't want to make a big deal of it. Ty, especially, was annoyingly dismissive. Pete kept saying, "Come on, let's play.

Rose, take your turn. I've heard enough about this goddamned wedding to last me the rest of my life." He was winning. He had all the green properties and Boardwalk, plus all the railroads. The dice were working for him, and we kept landing on his properties. Every time he laughed in greedy glee, I got more irritated. Ty was driving me crazy, too. He kept muttering, "Ginny, settle down." I blazed a couple of looks at him, but he didn't pay any attention. Rose and I locked eyes across the table just as Pete and Ty spoke simultaneously.

Pete said, "My turn, pass Go, collect two hundred dollars! Yeah!"

And Ty said, "I think if we all just concentrate on the game we'll have a better time."

Rose said, "Aren't you having a good time, Ty?" in a sugary and deeply sarcastic voice, and Ty, taking her seriously, began, "Well, not really-" and the mere fact that he couldn't read her tone of voice was the last straw for me, and I said, "My God!" with evident exasperation.

The Georges and the Jewels

The Georges and the Jewels Pie in the Sky: Book Four of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch

Pie in the Sky: Book Four of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch Duplicate Keys

Duplicate Keys Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens Good Faith

Good Faith Private Life

Private Life A Thousand Acres: A Novel

A Thousand Acres: A Novel The Greenlanders

The Greenlanders Ten Days in the Hills

Ten Days in the Hills Gee Whiz: Book Five of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch

Gee Whiz: Book Five of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch A Thousand Acres

A Thousand Acres The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton

The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton Ordinary Love and Good Will

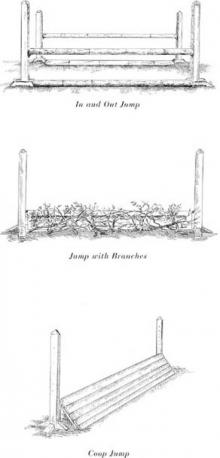

Ordinary Love and Good Will Taking the Reins (An Ellen & Ned Book)

Taking the Reins (An Ellen & Ned Book) The Man Who Invented the Computer

The Man Who Invented the Computer Horse Heaven

Horse Heaven The Age of Grief

The Age of Grief Riding Lessons

Riding Lessons Perestroika in Paris

Perestroika in Paris A Good Horse: Book Two of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch

A Good Horse: Book Two of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch Saddles & Secrets (An Ellen & Ned Book)

Saddles & Secrets (An Ellen & Ned Book) Some Luck: A Novel

Some Luck: A Novel Champion Horse

Champion Horse Some Luck

Some Luck Gee Whiz

Gee Whiz Barn Blind

Barn Blind A Thousand Acres (1992 Pulitzer Prize)

A Thousand Acres (1992 Pulitzer Prize) Pie in the Sky

Pie in the Sky True Blue

True Blue A Thousand Acres_A Novel

A Thousand Acres_A Novel A Good Horse

A Good Horse