- Home

- Jane Smiley

Barn Blind Page 17

Barn Blind Read online

Page 17

“You only had a five. Here’s your change.” The bills Henry handed her were flat and smooth. He had too much respect for money to wad it up the way John and Peter did, or to stuff it, uncounted, into a pocket. He kept it neatly in the top drawer of his dresser, and he had seventy-three dollars and thirty-four cents. Now, besides mother, the only person who owed him anything was John, five dollars. Mother’s debt was a dime she had borrowed for the mailman, and he didn’t expect to get that back, though it was hard to stop thinking about it.

Henry had fixed his final plan. On the second day of the family horse show, a day of the utmost conceivable chaos, he would gather up his provisions, pack his raincoat, and pedal away.

Casual requests, which had been sufficient with Peter and Margaret, had no effect on John, who said that if Henry made a pest of himself he would get pounded, because some people had a lot of things to do before the horse show. Henry recognized the validity of this argument in terms of their fraternal relationship and the weight and height John had over him, but he was nonetheless determined, the next morning, to risk the pounding and chance the repayment.

“I want my money,” he said, when they went first thing to bring in the geldings. This he had not said for two days, so he figured it was safe to be direct.

“You do, huh?”

“Yes. You said you’d give it back as soon as we got home from the show.”

“Is that what I said?”

“Yeah.”

“Didn’t you ever learn not to pay attention to what I say?”

There was no answer to this, so Henry reiterated, “I want my money.” Then, after a pause, “It’s my money.”

“There they are. You go around that way.” The geldings had stationed themselves in the woods overlooking the creek, deep in shade and still cool. There had been no rain in about two weeks. Henry circled around behind the animals; they were not as gullible as the two-year-olds, and lately had had to be chased in. “Hyah!” he shouted. Heads jerked up, more annoyed than surprised. Through the trees came John’s yell. “Git! You, too, Snip.” One or two started trotting. “Hyah! Hyah!” shouted Henry, laying his lead rope across Mr. Sandman’s flanks without a flutter of nostalgia. The remarkable self-sufficiency of the bicycle, which had neither to be fed nor entered in competitions had entirely removed Mr. Sandman from his heart.

The way John looked, twenty yards away, short, wiry, dark, and almost muscular, was the way Henry would look in three years. The clothes John was wearing, in fact, Henry would be wearing himself someday, except that he was about to take himself out of the hand-me-down rankings. John’s strides were short and his mannerisms energetic. These would be Henry’s too, with modifications in the direction of carefulness and conservation of effort. Everything that had been John’s became Henry’s, and he didn’t mind. Sometimes, when he thought about John and about his imminent departure, it seemed as if he would continue to live here after all, as much of him as was necessary.

“You’re going to go in the family class, aren’t you?” said John, when they were walking in behind the geldings. The family class took place toward the end of the second day. Though of course they had never won (mother had an agreement with the judge), the Karlsons had ridden in the family class every year since the first show, when Henry was two and rode on the pommel of mother’s saddle. He had forgotten. When he hesitated, suddenly panicked about his plan, John went on, “Shit, even dad goes in the family class.” It was true. Every year father got out his woolen breeches and brushed off his old coat and walked, trotted, and cantered around the ring with the rest of them.

“Sure.”

“She’s not going to make you pay an entry fee, tightwad.”

“I know. Say, speaking of that . . .”

“There’s Lucky heading for the creek. You’d better get him while I drive the rest of them in.”

“You get him.” But this was perfunctory, uttered in the very act of pursuit. He mostly, after all, did what John said.

He came to the warm-up ring just as John was mounting up; his shout, intended to preface a demand for payment at lunchtime, went unheeded. He went and found his bicycle.

It was midsummer hot, but he was industrious in his pedaling, squinting his eyes against the glare and wrinkling his nose against the dust. His body had changed in the last month. Muscles were more visible, and veins spread angular and soft, like gopher tunnels over his forearms. The thought of leaving did not please him although it did not exactly frighten him, either. For the most part, he could imagine nothing beyond bicycling down the road, and that he had done enough now not to thrill to it. He was apprehensive of large dogs, lightning, and groups of jeering older boys, but not of solitude, distance, or running out of money (people, he assumed, would be quite willing to give money to a twelve-year-old boy in return for less work than his mother got for free). Separation from the family did not intimidate him, and from this he divined that he must not like them very much. He was confident that he could manufacture a convincing story if he had to, and that the story would arise out of the demand itself, a perfect flower of a story, complete, credible, having even a bit of grace.

He pedaled up the two hills and coasted down, not too preoccupied with the future to fail to enjoy the exhilaration and danger of the small bridge. Just as he had never been anxious about Christmas or his birthday or the end of school, just as he had awaited those days with equanimity and greeted them with a quiet sense of achievement, now he was not anxious about his new life. He expected to become, eventually, rich, powerful, and grown-up. He expected to eat many delicious meals. He expected to begin upon these accomplishments very soon, since, as he knew what he wanted, there was no reason to delay. He expected to remain single-minded, calm, and detached for the rest of his life. He expected the mainspring of the farm to tick forever, and to measure his days to those regular ticks, which he expected never to lose the sense of. To anticipate that morning, four days hence, to get excited, to smile to himself, to lie awake, would jeopardize the inevitability of everything, and so he pedaled and coasted, and pedaled some more, and at lunchtime went home for his usual peanut butter sandwich. While he was dipping up the grape jelly, John banged into the kitchen, and it came to Henry that he was going to neither speak of nor expect the money, that this decision was irreversible, and that there was something about his relationship with John which he did not now understand but one day would.

9

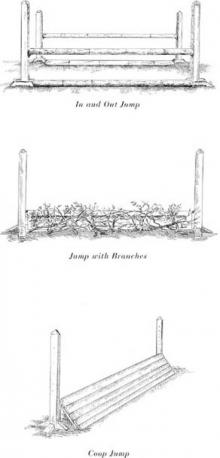

BESIDES riding, they recovered, then painted and repaired all the jump poles and standards on the farm. New ones were ordered from the lumber yard and delivered, as well as three new panels and a new chicken coop. Kate closed her eyes at the expense. The scattered logs of many log jumps on the outside course were gathered together and stacked imposingly. The brush jumps were newly filled with brush, old hay-bale jumps remade with fresh, square bales. Oddities were contrived. Father got out the tractor and pulled a huge log into place over a trail through the woods. John and Peter tacked together an old five-barred gate. Louis came back to the farm for two days to mow all the pastures to a prosperous yellow-green. Two cracked panes of glass in the main barn were repaired, and Axel, in an extravagant mood, replaced the baling-twine gate fasteners with chains and hooks. Pony Clubbers came to brush and braid their mounts three days in advance, just so the braids would fall out and they could do it again. Saddles were soaped, saddle blankets taken to the laundromat in town and put in the heavy-duty machines. The dishes were left undone, the beds unmade, the family’s underwear unwashed.

John and Peter shoveled out the visitors’ stalls and planned where they would hide the family tools so that strangers wouldn’t carry them away. The scoreboard for the combined event was whitewashed, the lines redrawn. The judge’s tent was rented (this year green and white) and chairs were found and tables and pads of paper and extension cords. Pony Club mothers agreed to take care of refreshments, fought over the inclusion of diet soda pop, decided in favor of popularity over nutritional value, and

sent their husbands over with great tubs for ice. The man with equipment for hotdogs and hamburgers appeared, set up the equipment, and left. Three Pony Club mothers and seven Pony Club siblings wrapped a thousand cheese sandwiches, all with mustard, none with mayonnaise. The screen door banged continually. Mother was everywhere, as calm as possible, having no effect on the chaos.

Riders continued their daily lessons, now beginning at seven, to leave more time for preparations. As the show approached, the show in which they were to compete, the Pony Clubbers became insensibly overawed with Peter. They spoke always about how good he really was, how the judge, a retired member of the Team, was really coming to see Peter in action more than anything else. It was felt privately that this man of wisdom might pick one of them out of the crowd as well, see nascent genius among the beginners as only fresh, unprejudiced eyes could do.

Expectations of the man’s infallible wisdom rose and rose as Peter’s private lessons with his mother lengthened. Obviously she was grooming him for something. John was not the only one who casually strained his sight in their direction as he went about his chores, nor the only one whose every encounter with Peter was fraught with unasked questions about what mother had said, promised, and prophesied. To John it seemed that there must have been some note to this judge, some postscript instructing that he look especially closely at mother’s oldest son, and he ground his teeth at the thought. He imagined a tunnel vision that would inexorably exclude his own claims for notice. He felt it had been unfair of mother to prejudice the observer before he even came, before he had a chance to look around and draw his own conclusions. If anything, he felt, Peter ought to have been handicapped somehow, since he had the flashiest horse. The judge would certainly notice Peter. The person he should be encouraged to notice was John himself, who was doing excellent things with an indisputably second-rate mount.

Peter, whose focus had narrowed considerably, almost totally, saw nothing but MacDougal; Mac he saw with a depth of field that was exhaustive and crystal clear. He had come to function as the perfect pivot point between the voice of his mother and the energies of his horse. Twenty-one hours a day he seemed about normal. He did his share of the work and the joking and the squabbling. He flirted absent-mindedly with the girls, giving the usual impression that he wasn’t aware of flirting, and therefore having great success. But his mind, more than ever, was on something else (and his mind had dwelt on many other things than the business at hand for as long as anyone could remember). It was on MacDougal.

During riding class he had usually, at least more than any other time, paid attention. Now, however, his attention was ferocious and continual and inarticulate; he could not be said to be thinking about riding, if “thinking” was to imply something to do with words. Although he read the anatomy book and memorized the terms, although he read the other books mother assigned him, and then answered her questions when she quizzed him during their afternoons together, and although her endless flow of talk was as the air itself, he understood nothing in terms of words and everything in terms of the way his bones and muscles and eyes and hands encountered the horse.

“Think of the cannon bone,” said Kate. He was trotting around the warm-up ring. He thought of the cannon bone—straight from knee to ankle, simple, solid, guyed with ligaments and tendons. “What is the cannon bone doing now?” said Kate. “And what is the cannon bone doing now?” (He halted, he cantered forward, he took a small fence. MacDougal’s four cannon bones flashed rhythmically and dependably in the sunlight.) And the cannon bone was by far the simplest of them all. The hoof, for example, was enough to boggle the mind. He hardly heard her questions, hardly heard his own answers, but their effect was to etch the drawings he had looked at into his memory, and further, to endow them with movement and meaning. These days MacDougal amazed him.

Success, compared to this—that is, the success of blue ribbons and praise from ex-members of the Team—was laughably irrelevant, and yet to all appearances he was bent on exactly that sort of success, and it was clear even to him that it would be forthcoming.

To John it was even clearer. Teddy groaned and farted and schemed for snatches of grass that showed green at the corners of his bits, looking untidy. He rubbed his enormous head against fenceposts and passersby, pulling strap ends out of their keepers and disarranging his bridle. He closed his eyes, hung his head, and resembled a plow horse. He rubbed John’s careful braid out of his tail, breaking the hairs and making it impossible to rebraid. Everything that was done had to be done over. Nothing that was done enhanced Teddy’s looks, and so nothing that was done brought esthetic pleasure. John smacked him with his hand, berated him, vented upon him the full force of his exasperation. Astride he had formed the habit of covert but abandoned vehemence, and it was an intoxicating habit.

During every lesson, John’s turn came right after Peter’s. In every group movement, he was to keep his eyes on MacDougal’s beautiful hindquarters and silky tail, to keep his distance, but not to lag behind. After Peter galloped over a short jump course in perfect style and balance, he was to do the same. It was clear he could not hope to do better. How, he thought, had Peter, who had been just another of them two months before, grown so fair and golden, so graceful and precise, in a mere number of days? How did days add up in this way?

John spurred Teddy and held him in. The horse arched his neck and approached for a moment the condition of having flair. The horse lagged. If mother wasn’t looking, John fluttered his whip, a proscribed behavior because it made horses whip shy, and, eventually, insensitive; the horse perked up. Peter made no mistakes. He held his hands low and quiet. He indicated gait and directional changes by a shift of weight. The small of his back, always within John’s purview, flexed like a bow. His shoulders floated, his neck floated, his chin floated, his horse floated. His hair ruffled in the breeze, he was fair and beautiful. John had only two choices: to love his brother and hate himself, or to hate his brother and love himself. Mother shouted at him to pay attention, for goodness’ sake, he was sticking his chin out from here to Buffalo. He realigned himself with a start, and Kate considered, with pardonable pride, that her judgment about Teddy had been just right. John was definitely shaping up, yes indeed. She smiled. He hadn’t grown a centimeter since Christmas, either.

Everything, fortunately, had gone wrong. Kate was at her very best. From insufficient extension cords for the announcer’s stand to questionable mayonnaise on a hundred and twenty-four tunafish sandwiches (Henry, who had sneaked the hundred and twenty-fifth, was being watched carefully for symptoms. He told everyone he encountered that it had tasted all right to him). Kate was commanding, shining with hospitality, as manly as a cavalry officer in her pressed shorts and crisp madras shirt. Like everyone else, Axel wished to follow her around, asking for orders and reassurance. Pony Club mothers and fathers, in feed caps, bermudas, and short-sleeved shirts, were being greeted and blessed continually, whether they brought station-wagons full of cold lemonade or only themselves and their bright-faced daughters. Kate alone blazed with the capacity to bring order to everything, and even Axel was prey to the twenty-year illusion, although it was he who knew where the extension cords should be, and he who ordered the sandwiches thrown out, correctly estimating the cost of even the slightest risk.

This was hardly the first show he had stayed home to help with, but it was the first to move more than his sense of duty. Usually, crowds of people roaming the farm offended him. They did not so much endanger things (fences, equipment, livestock, themselves) as they violated the place and weighed it down. Every year after the horse show, there was more dust and less greenery, the lingering odor of automobile exhaust and the belongings of strangers (women’s underwear was the most offensive). When objects of value were lost (every year someone’s watch, someone’s paycheck), the item in his imagination seemed to erode the ground it lay on, and he was unwontedly angry, as well as assiduous in directing the search.

This summer, however, the inconve

niences of the horse show were secondary when he thought of them at all. What he anticipated was the fascination of watching his wife for three days straight, of catching her eye, of paying sudden attentions to her that would make her mispronounce a word or blush or forget who had just spoken to her. His flirtation of late had gone so well that he was wildly curious to pursue it, the more so because in her way she was pursuing it too. When she looked at him, he saw what he expected in her face: recognition, curiosity, and the resigned dread of a child diving off the high board. He exulted and pretended to see nothing, waiting within the shell of their customary relationship for her to get fed up or bored or anxious, waiting for some impatience that he could turn to his own advantage. He suspected that the chaos of the horse show might bring it about. He knew that, in spite of her crisp shorts and spruce shirt, her effusive attention to riders and parents and potential customers, it was him she was thinking of.

She was standing in the way of the doodad drawer in the kitchen, where they kept string and toggle bolts and extension cords. “Excuse me,” said Axel.

“Yes?” She looked up beaming, expectant. Probably, he thought automatically, taking him for a child or some Pony Club father.

“I need to get in there.” He motioned at the drawer.

“Oh, really! Of course! Let me get out of the way.” She continued to smile and failed to move.

“Well, get out of the way.” At his smile they were embarrassed, and she went back to writing her note while he rummaged for a fourpenny nail. He found it, looked for another one, noticed that she had started to doodle on the note. Now she wadded it up and wrote again, but still it was difficult, impossible, to speak.

“I want Henry to keep Talbot and the announcer supplied with cold drinks,” she said. “He isn’t riding, after all.”

The Georges and the Jewels

The Georges and the Jewels Pie in the Sky: Book Four of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch

Pie in the Sky: Book Four of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch Duplicate Keys

Duplicate Keys Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens Good Faith

Good Faith Private Life

Private Life A Thousand Acres: A Novel

A Thousand Acres: A Novel The Greenlanders

The Greenlanders Ten Days in the Hills

Ten Days in the Hills Gee Whiz: Book Five of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch

Gee Whiz: Book Five of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch A Thousand Acres

A Thousand Acres The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton

The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton Ordinary Love and Good Will

Ordinary Love and Good Will Taking the Reins (An Ellen & Ned Book)

Taking the Reins (An Ellen & Ned Book) The Man Who Invented the Computer

The Man Who Invented the Computer Horse Heaven

Horse Heaven The Age of Grief

The Age of Grief Riding Lessons

Riding Lessons Perestroika in Paris

Perestroika in Paris A Good Horse: Book Two of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch

A Good Horse: Book Two of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch Saddles & Secrets (An Ellen & Ned Book)

Saddles & Secrets (An Ellen & Ned Book) Some Luck: A Novel

Some Luck: A Novel Champion Horse

Champion Horse Some Luck

Some Luck Gee Whiz

Gee Whiz Barn Blind

Barn Blind A Thousand Acres (1992 Pulitzer Prize)

A Thousand Acres (1992 Pulitzer Prize) Pie in the Sky

Pie in the Sky True Blue

True Blue A Thousand Acres_A Novel

A Thousand Acres_A Novel A Good Horse

A Good Horse