- Home

- Jane Smiley

True Blue Page 9

True Blue Read online

Page 9

For the moment, though, it seemed as though all he cared about was the hay. I left the stall, hanging his beautiful halter there on a hook, and headed for the house. When I stepped up onto the back porch, as I was giving Rusty a pat on the head, I turned and looked back. Blue was pressing his chest against his stall door and staring at me.

Saddle with Strings

Western Fleece Cinch

Chapter 10

MOM BROUGHT MY JEANS AND BOOTS WITH HER WHEN SHE picked me up at school the next day, and also a jacket because if it was misty around the school, then it was certainly rainy at the stable. But she hadn’t gotten any calls from Jane saying not to come. She said, “They don’t care about the weather out there. They just put on their raincoats and ride, like in England. How does your arm feel?”

I shrugged. Fortunately, my jacket had a pretty wide sleeve, so I could get it on, and then put the sling around that. When we got there, it was the same weather as at school. It was just after three-thirty, and the sun would be going down around six, so we had enough time. Especially since Rodney Lemon put his head out of Gallant Man’s stall as soon as he heard my voice and said, “Ah, there ya are, lass. Here’s the pony.” He opened the stall door and led him out.

Only a year before, I’d ridden Gallant Man in a show—my first at the stable—but it would have been hard for me to ride him now, he had gotten so small. Or I had gotten so tall. While I was staring at him, Jane came over with Melinda. Melinda was now maybe ten, but the only thing different about her was that her hair was longer. She ran up to me and gave me a hug. She said, “Oh, Abby, I missed you! What happened to your arm? Jane said you broke it! I hate Los Angeles! I’m so glad we’ve moved up here. We have a new house, did you know that? And I have a new school where there are NUNS and it’s much better.” She put her arms up and pulled my head down and whispered in my ear, “I have to do fourth grade again, but I don’t care! I didn’t listen to a word they said at my school in Los Angeles.”

I said, “I’m glad to see you, too, Melinda.” She kissed me on the cheek.

And all of a sudden I was glad to see her. Rodney lifted her onto the pony and I started walking toward the ring. Melinda on Gallant Man walked beside me, and Jane walked behind them. We went to the smallest ring, which was empty. I opened the gate. Melinda said, “I want to hear all about how you broke your arm. I do so hope it wasn’t falling off a horse, because I don’t want to think about that.” I didn’t tell her, and she kept talking. “My mom had to stay in LA, but May and Martin came along, and she takes care of me and he drives me to school.” She stopped Gallant Man in the center of the ring and took her feet out of the stirrups. I bent down and checked to see how long they were. I decided that they were too short and began to adjust the left one, which was awkward and slow with one hand. She said, “May lets me do whatever I want, but I never want to do anything bad.”

I said, “I’m sure you don’t, Melinda.”

I went around and adjusted the right stirrup, then had her stand up in them. Maybe she had grown. I said, “Walk him out on the rail, Melinda, and let me see how you’ve gotten better.”

I wouldn’t have said that Melinda had improved much, but she’d always been more skillful than confident. Now she picked up her reins and gave Gallant Man a kick. When they were out on the rail, I could see that her heels were down, her thumbs were up, and her back was straight without being arched. I called, “Don’t stick your chin out, Melinda. Just let it float along like a flower.” Her head turned on her neck a bit, and then she did it.

Even when they are lazy, most ponies don’t look lazy—they look perky and bright, as if somewhere, there is a horse who needs to be told what to do, and if the pony is lucky, that horse will appear any minute. That’s how Gallant Man looked just then. I called out to Melinda, “Shorten your reins about an inch, so that he brings his chin in a tiny bit, but squeeze your legs while you’re doing it, so that he knows that you don’t mean to stop him.” She did all these things.

Jane was standing beside me with her hands on her hips. She said, “Such a custody battle! It’s like nuclear war! Now she’s with her dad, but I don’t know—”

“Who’s May?”

“May is the housekeeper, and in my opinion, she’s the only one who actually cares about the child. She’s married to the chauffeur. He brings her out here.”

“What’s a chauffeur?”

“Someone who drives the car.”

I tried to imagine Daddy allowing some stranger to drive either the car or the truck. It could not be done. Jane said, “Well, good luck. I’ll come back in a little while to see how you’re doing, but I’m sure you’ll be fine,” and she walked away.

I called out, “Okay, Melinda. I want you to do three things in a row. I want you to turn the pony in a small circle, then I want you to trot for fifteen steps, then I want you to halt.” As she did this, I realized that this was what she needed. When she had halted, I went over to her, and I said, “Okay. We’re going to play a game.”

“I love that,” said Melinda.

“Here’s the game. You are going to count to ten—fairly slowly, like this.” I counted to ten. “At the beginning of each count, you are going to do something, like walk out or trot, and when you get to ten, you are going to change what you’re doing to something else. You can do anything you want, walk, trot, canter, halt, back up, trot faster, walk slower, but it has to be different enough from the last thing so that I can see that it’s different. Okay?”

She said, “Can I have points?”

“Sure. One point for making a change, one point for making the change right on ten.”

“What about two points?”

I thought for a second, then said, “Next round, I’ll give you something to do for two points.”

She said, “Okay, tell me when I get to fifteen points.”

I hadn’t thought of that. I said, “Okay.”

She gathered the reins and trotted away. I could hear her saying, “One, two, three …” I went back to the center of the arena.

I could see Melinda’s lips moving, so I tried to count along with her, which I hadn’t thought of when I was making up the game. She was pretty good—she walked, then trotted, then turned in another circle, then trotted more quickly, then walked, then halted, then trotted, then cantered, then walked and turned to go the other way. Every so often, I called out “Heels down!” or “Sit up!” or “Don’t forget to look where you’re going!” She was a little slow on a couple of the changes, but she got to fifteen points, and I called out, “Okay! Fifteen points.”

She laughed and came trotting over to me. She said, “Can I do it again, but jump something?”

“Do you really want to jump something, Melinda? You used to be afraid of jumping.”

She nodded. “I’ve been jumping with Jane for the last few weeks.”

I saw a little crossbar in the middle of the ring, not more than a foot high, and pointed to it—I was glad I didn’t have to build a jump myself with only one hand. Before she started again, I said, “If you make a good jump, you get two points, but if you make a bad jump, like if you’re left behind or you get ahead, then you lose two points. That means that your score can go way down for bad jumps.”

She grinned and nodded even more enthusiastically. I said, “Melinda!”

“What?”

“Don’t forget to pat your pony!”

She put her hand down and patted Gallant Man on the neck. I said, “If you pat him right after he’s done something good, you get an extra point.”

This game worked out even better—we went to twenty-five points, and Melinda jumped the crossbar four times, but only when she wanted to. She stayed right with the motion, too, neither leaning ahead of the pony nor getting left. The rest of the time, she did sharp transitions—even one from the walk to the canter, which is a little harder than from the trot to the canter. When we got to twenty-five points, Gallant Man was puffing a little bit, so I made

her walk him around on a loose rein for a while. All told, she remembered to pat him five times. I said, “Melinda, you are pretty brave these days.”

She said, “I like to do what I want.”

“Isn’t that the truth,” said Jane Slater, who was coming into the ring.

I said, “This is pretty fun. Do we have time to do it again?”

Jane shook her head. “We have to get her out of here in some way before you know who arrives.”

I said, “Really?”

“Really.”

“When does she arrive?”

“Ten minutes.”

I walked over to the pony and said, “I know a back way to the barn. We can go on the trail.”

“I don’t like to go on the trail.”

“I’ll go with you. You can keep playing your game. We’ll start down the trail, and I’ll go behind you, and everything you do, I’ll do, too.” I figured I could keep up with Gallant Man.

“No, you go in front.”

I said, “Okay,” and I ran out the gate. Melinda laughed as she trotted after me. By the time we got back to the barn, I knew she’d been right not to go ahead of me—I had to sit down on a tack trunk, I was breathing so hard. And my wrist was throbbing. Gallant Man could easily keep up with me, but I would not have been able to keep up with him. Melinda came over to me and gave me a hug and said, “Thank you,” and then Rodney handed me the pony’s reins and spirited her away to the Coke machine.

Of course, now I figured I knew everything about teaching horseback riding. Ellen Leinsdorf wasn’t so sure. The first thing she said when she saw me was, “Why isn’t Jane teaching me?”

“She said I—”

“What’s wrong with your arm?”

“I broke it.”

“I bet you fell off a horse. Were you jumping?”

“No, I—”

“I’ve never fallen off a horse.”

“Everybody falls off eventu—”

“I never have. I’m not going to.”

I looked down at her. Her two braids were like sticks, they were so stiff. I said, “You know what my daddy always says?”

“What?”

“You aren’t good until you’ve hit the ground three times.”

“I don’t believe that.”

Even though she was shorter than Melinda, she walked up to Gallant Man, gathered the reins, put her hand way up on the cantle of his saddle, and mounted from the ground. Then she checked and shortened her own stirrups, and even leaned down and checked to see if her girth was tight. I was impressed. She shook her shoulders, settled into the saddle, and said, “Let’s go to the ring. I only have forty-five minutes. I want to jump.”

She walked away from me, and I trotted after her to catch up. When we got to the ring where I had been teaching Melinda, I opened the gate and said, “Do you jump with Jane?”

“Sure.”

“Show me jumps you’ve jumped.”

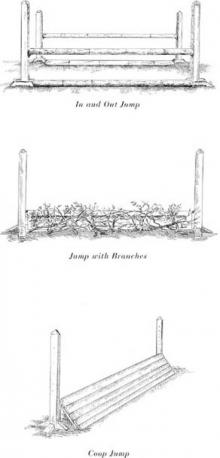

Without hesitating, she pointed to a brush and a coop, both of which were maybe two foot six, and a somewhat larger panel that was leaning against the fence. I said, “That’s pretty big.”

“That’s why I like it best.”

As I closed the gate, she trotted away from me. I went to the center of the arena and watched her for a minute. She did have her heels down, but they were way down, so far down that I couldn’t believe that her ankles had that much stretch in them. But everything about her riding was exaggerated—she held the reins too tight, kicked the pony too hard, arched her back, held her chin too high. I called out, “Turn and go the other direction!” Her turn was abrupt, and the pony tossed his head. She trotted the other way. I watched for another minute, until she shouted, “Tell me to do something!”

“Halt!”

Not a good idea. I almost had to hide my eyes as the pony lurched to a halt. Ellen’s braids didn’t move, though. I looked around for Jane, but she was nowhere to be seen. I walked over to Ellen.

With her on the pony, we were eye to eye, and she stared at me. I said, “Ellen—”

“What?”

“I want you to practice being nicer to the pony. He’s trying to be good.”

“I am nice to the pony.”

“Well, loosen your reins a little.”

She loosened them about a quarter of an inch.

“No, really. More than that.”

Another quarter of an inch.

“Look at his head. You’re making him stick his neck up in the air. It’s like if I had to walk around like this.” I bent my head back and walked around looking at the sky for a couple of seconds.

She loosened another quarter of an inch. I took hold of the left rein down by the bit and said, “Let go of the reins completely for a second.”

“He’ll run away.”

“No, he won’t. I’ve got him.”

“I wish I had a grown-up teaching me.”

I thought, The grown-up doesn’t want to teach you, and I knew this was true.

“We can have plenty of fun.”

Her lower lip pushed out.

“Can you let go of the reins for a minute?”

She waited, and then dropped the reins. I positioned myself next to her leg, facing toward the front, and then I picked up the reins so that I was making contact with the pony’s mouth, but not pulling on it. The reins were nice—old and well used. I said, “Can I have the ribbons from your braids?”

She said, “Yes! I hate these ribbons. I hate pink.”

I thought, I bet you do. I untied the ribbons, then tied one to each rein where I thought her hands should go. Then I said, “Okay, you put your hands on the ribbons, and make sure they’re always covered up. I don’t want to see them coming out behind your hands or in front of your hands.” I set her hands on the reins the way I thought they should be, with the ribbons inside her hands, and said, “Okay, now walk.” She walked away. The pony looked much more comfortable. It was a good thing the ribbons were pink, because I could see them every time she moved her hands. After a moment, I told her to trot. That seemed to be harder, because she wanted to shorten the reins and hold on. I called out, “I see pink!”

Ellen scowled.

I said, “Keep trotting!”

And again, “Keep trotting.”

But she was determined, I have to say that. It took her about twice around the small arena with a real scowl on her face and her shoulders hunched before she realized that she was doing fine, and it was easier than she thought. I called out, “Make a nice turn and go the other direction!”

She made sort of a nice turn, but she did go the other direction, and after about half a circuit, she relaxed going that direction, too. I let her go one more circuit, then I called out, “Okay, walk! But just sit down in the saddle, don’t pull on the reins!” She managed to do this. I went over to where she was walking the pony and said, “Now pat your pony.” She put both her reins in one hand and reached around with the other one and patted Gallant Man behind the saddle once.

I said, “Pat him on the neck.”

She patted him on the neck.

I said, “Pat him on the shoulder.”

She bent forward just a little bit and patted him on the shoulder.

I said, “Pat him on the underside of his neck with your other hand.”

She switched hands on the reins and reached under his neck.

I said, “Pat him on the cheek.”

She did the right thing—she halted him, then turned his head toward her slightly with one rein, and patted him on the cheek.

“Now the other side.”

She did the same thing on the other side.

I said, “He’s a good pony.”

“I love him.”

“Did you really jump that brush and that panel?”

She shook her head.

“Did you jump anything?”

She shook her head again.

“Well, let’s do it.”

“Really?” Now she grinned for the firs

t time the whole lesson.

“Yes, but I’m going to move your ribbons.” I moved the pink ribbons forward about an inch and a half and said, “I’m going to lead you over the crossbar, there, and the pony’s going to trot. You stand up in your stirrups and put your hands with the reins right here on this place on the mane”—I made a little braid—“and just hold on right there the whole time, okay?”

She nodded. I took the pony by the bridle and trotted toward the crossbar. It was a good thing my right wrist was the unbroken one. As we were trotting, I turned and looked at Ellen. Her lips were pursed and she was trying hard to keep her balance. I said, “Hold on.”

She tightened her grip. When I jumped over the crossbar and the pony jumped right next to me, her mouth opened in an O.

We slowed to a halt. Ellen sat down. I said, “Want to do it again?”

She nodded.

“Are you holding on?”

“Yeah!”

I almost laughed. “Heels down!”

We jumped the crossbar again and came down to a halt.

Ellen said, “You go right there, by the standard. I want to do it.”

“Let me take you once more, but not holding the bridle.”

We did this.

Then she did it once in each direction on her own. The pony was perfect. After the second time, Ellen rode the pony back to me and said, “I was really good, wasn’t I?”

I said, “Yes, you were really good.”

She grinned.

Then I heard, “Oh, my goodness! Oh, dear!” I turned. Mrs. Leinsdorf was hurrying in the gate. She said, “Ellen! You were jumping! Who is this child?”

“It’s Abby. She’s my new—”

“Well, Abby, I don’t know who you are, but Ellen does not have permission to jump!”

I looked around for Jane, then opened my mouth to say something, though I wasn’t sure what that was going to be. Ellen’s scowl deepened. She said, “Abby owned Onyx when he was Black George. She trained him. She lives on a ranch and she’s a great rider.” I would have been flattered by what she said, but she said it in such a threatening voice that I was more amazed such a small person would talk like that to her mother than I was pleased by the compliments.

The Georges and the Jewels

The Georges and the Jewels Pie in the Sky: Book Four of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch

Pie in the Sky: Book Four of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch Duplicate Keys

Duplicate Keys Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens Good Faith

Good Faith Private Life

Private Life A Thousand Acres: A Novel

A Thousand Acres: A Novel The Greenlanders

The Greenlanders Ten Days in the Hills

Ten Days in the Hills Gee Whiz: Book Five of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch

Gee Whiz: Book Five of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch A Thousand Acres

A Thousand Acres The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton

The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton Ordinary Love and Good Will

Ordinary Love and Good Will Taking the Reins (An Ellen & Ned Book)

Taking the Reins (An Ellen & Ned Book) The Man Who Invented the Computer

The Man Who Invented the Computer Horse Heaven

Horse Heaven The Age of Grief

The Age of Grief Riding Lessons

Riding Lessons Perestroika in Paris

Perestroika in Paris A Good Horse: Book Two of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch

A Good Horse: Book Two of the Horses of Oak Valley Ranch Saddles & Secrets (An Ellen & Ned Book)

Saddles & Secrets (An Ellen & Ned Book) Some Luck: A Novel

Some Luck: A Novel Champion Horse

Champion Horse Some Luck

Some Luck Gee Whiz

Gee Whiz Barn Blind

Barn Blind A Thousand Acres (1992 Pulitzer Prize)

A Thousand Acres (1992 Pulitzer Prize) Pie in the Sky

Pie in the Sky True Blue

True Blue A Thousand Acres_A Novel

A Thousand Acres_A Novel A Good Horse

A Good Horse